Masumi Hayashi

Large-scale photo collages that rupture documentary logic, warping time and space to transform intimate memory into social history

Explore by Series

193 panoramic photo collages across 8 thematic series

Japanese American Internment Camps

20 artworksSites of WWII incarceration where 120,000 Japanese Americans were imprisoned

Manzanar Internment Camp Monument

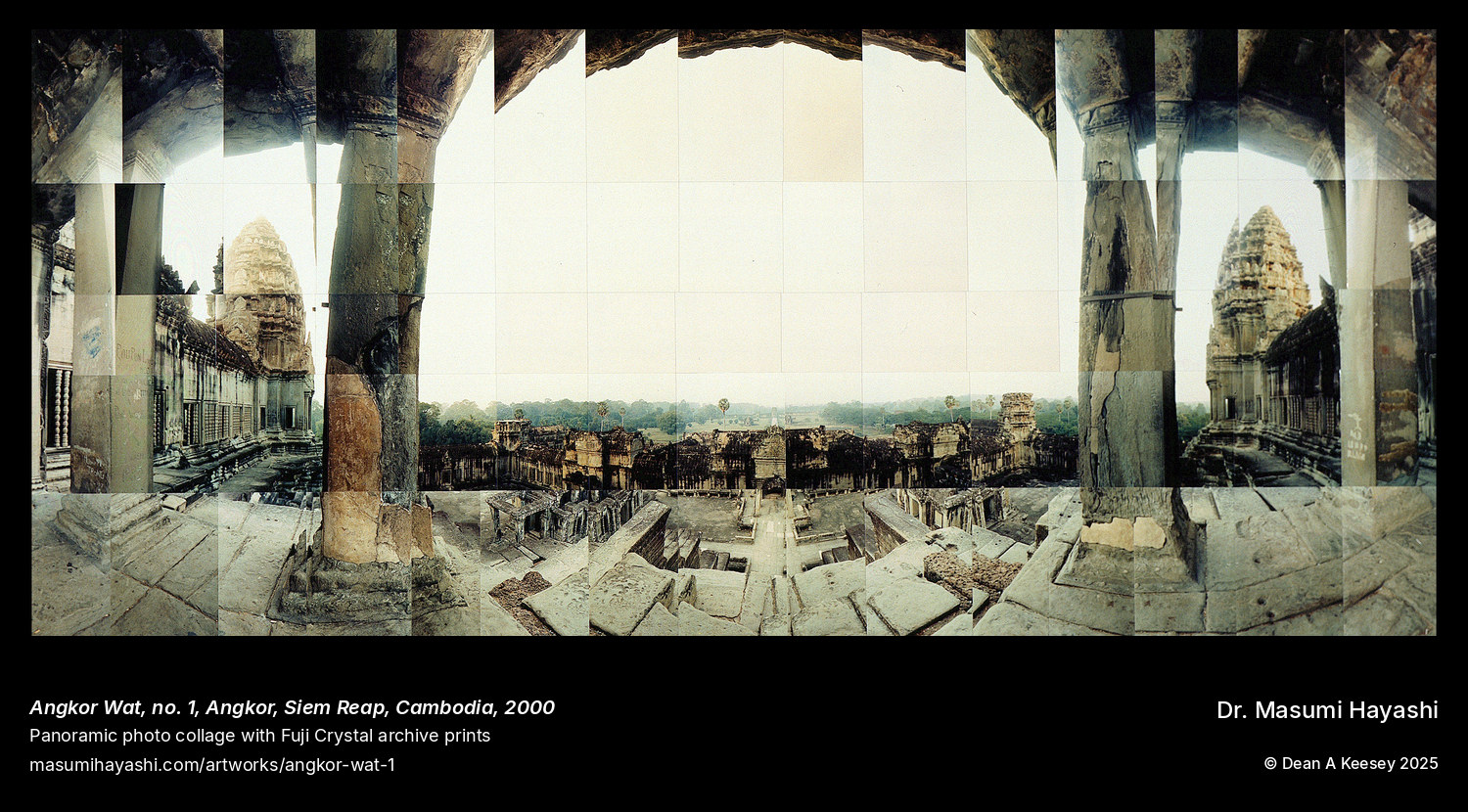

Sacred Architectures

43 artworksTemples and spiritual sites across Asia

Angkor Wat No. 1

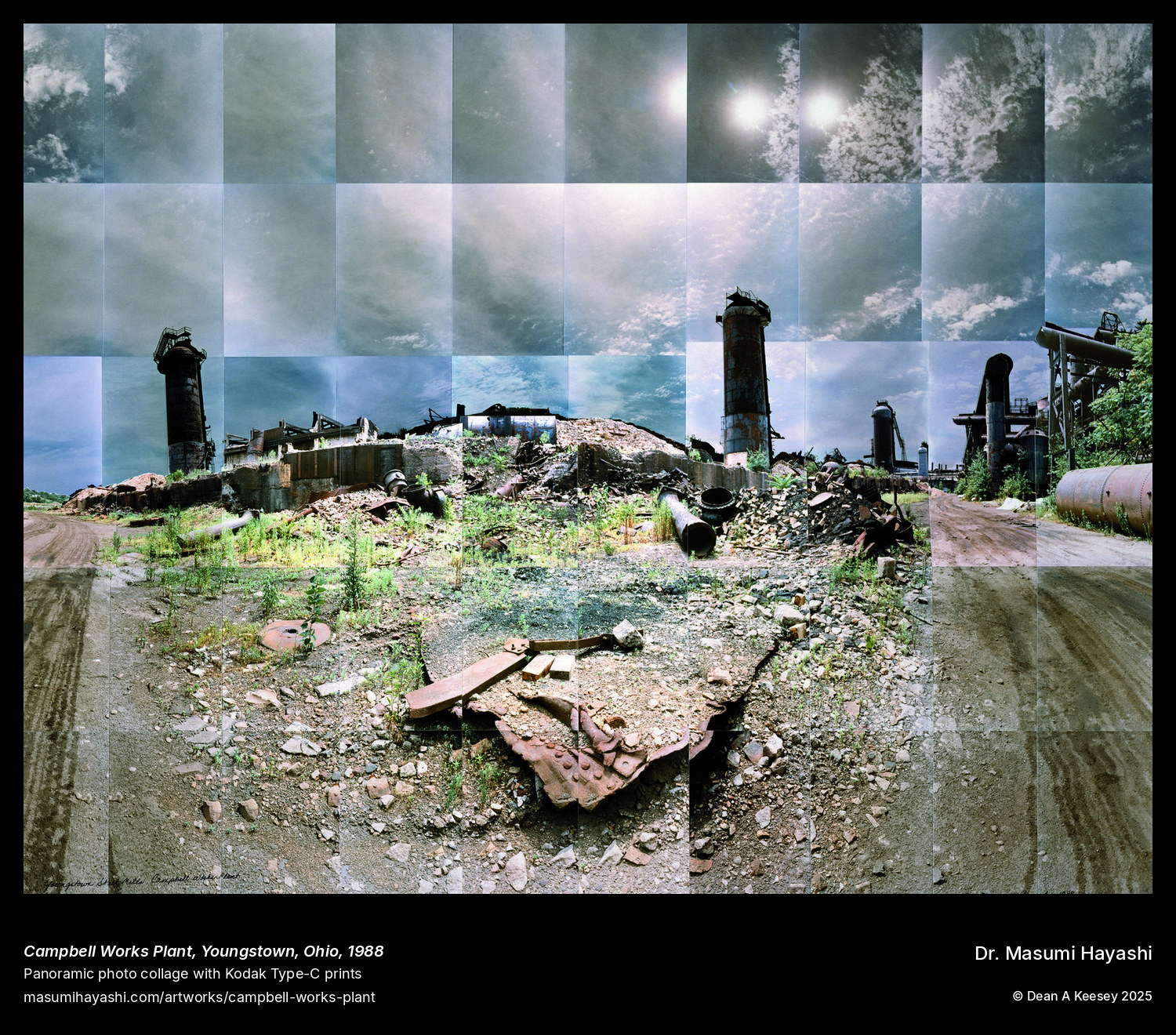

Post-Industrial Landscapes

24 artworksAbandoned factories and industrial sites across America's Rust Belt

Campbell Works Plant, Youngstown

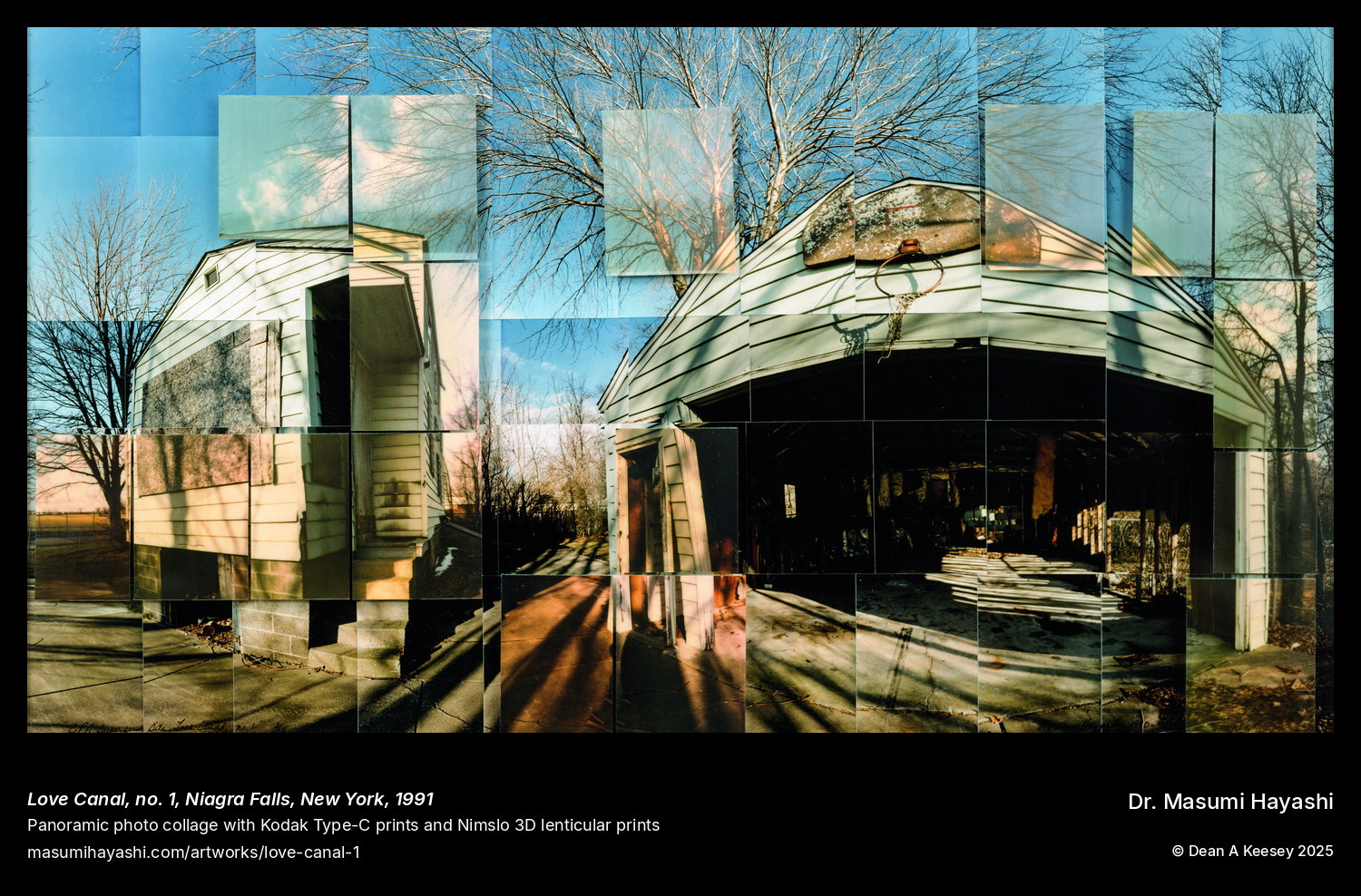

EPA Superfund Sites

16 artworksSites of toxic contamination and environmental cleanup across America

Love Canal No. 1

City Works

26 artworksUrban architecture and public spaces in American cities

Old Arcade, Cleveland

A Legacy of Artistic Testimony

Born in 1945 at the Gila River concentration camp in Arizona, Masumi Hayashi spent her life creating panoramic photo collages of the landscapes that shaped American history. Each work—assembled from 80 to 150 individual prints—transformed sites of confinement, environmental degradation, and cultural significance into powerful physical objects that rupture the logic of documentary photography.

As a Professor of Art at Cleveland State University for over three decades, Hayashi dedicated her practice to constructing large-scale works that explore places where trauma and memory intersect: Japanese American internment camps, abandoned industrial sites, toxic Superfund locations, and sacred architectures across Asia.

Her work has been exhibited internationally and is held in major museum collections including the Museum of Modern Art, Whitney Museum of American Art, and Smithsonian American Art Museum.

Support the Foundation

Your tax-deductible donation helps preserve and share Dr. Hayashi's artistic legacy for future generations.

Currently on View

Masumi Hayashi's work is featured in exhibitions across the United States

View Current Exhibitions →