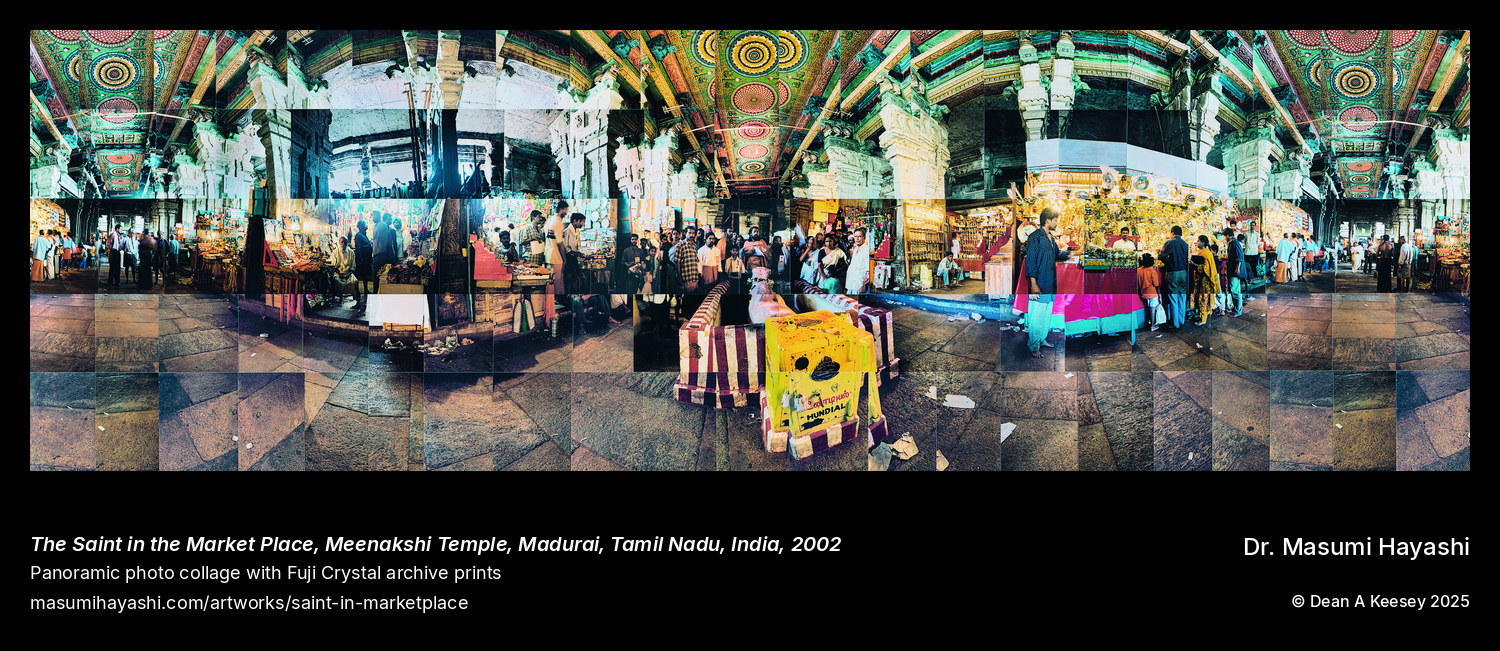

The Saint in the Market Place, Meenakshi Temple, Madurai, Tamil Nadu, India

Madurai, Tamil Nadu, India

Panoramic Photo Collage

2002

49" x 29"

This vertical 49-by-29-inch panorama documents an intimate devotional moment within Meenakshi Temple’s vast marketplace—one of three or four Meenakshi works representing Hayashi’s most comprehensive documentation of any single temple complex. The evocative title “The Saint in the Market Place” suggests capture of religious devotion amid commercial activity, the temple’s bazaars where sacred and secular commerce interweave inseparably.

Created in 2002 during concentrated Tamil Nadu documentation, the work explores Meenakshi Temple’s unique character as functioning religious city rather than isolated monument. The temple’s enclosed area spans fifteen acres, its corridors housing thousands of shops selling religious offerings, devotional images, silk clothing, jewelry, and daily necessities. Pilgrims navigate commercial chaos to reach shrines; merchants conduct business within sacred precincts; sadhus and devotees occupy spaces between vendor stalls.

The title’s “saint” might reference several possibilities: an actual wandering holy man photographed amid marketplace activity; a temple sculpture of one of the sixty-three Nayanar saints (Tamil Shaivite poet-saints whose devotion established the temple’s spiritual genealogy); or a devotee whose piety stands out against commercial surroundings. The ambiguity is productive—Hayashi’s title inviting meditation on sanctity’s persistence amid worldly distraction.

The vertical format emphasizes the crowded verticality of temple bazaar architecture—multi-story buildings pressing against corridors, goods stacked toward ceilings, visual density requiring upward as well as horizontal navigation. Unlike the architectural vistas capturing gopurams and thousand-pillar halls, this work documents the temple’s lived dimension, the daily commerce that sustains both institution and pilgrimage.

This intimate focus complements the series’ monumental documentation, recognizing that India’s great temples function as complete environments encompassing worship, commerce, social gathering, and artistic production within unified sacred precincts.