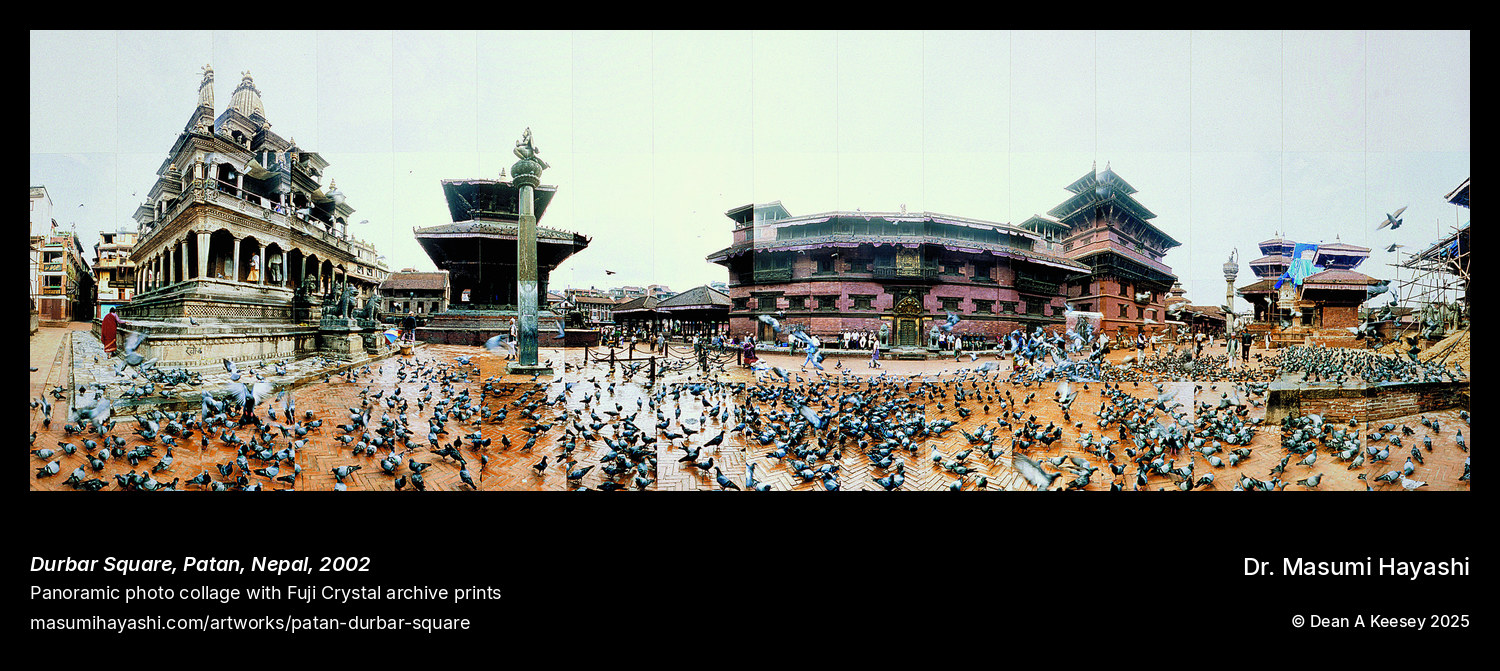

Patan Durbar Square, Patan, Nepal

Patan, Nepal

Panoramic photo collage

unknown

unknown

Patan Durbar Square exemplifies the Kathmandu Valley’s architectural genius—one of three royal palace squares where Malla kings competed through building rather than warfare. From the 12th through 18th centuries, rival kingdoms in Kathmandu, Patan, and Bhaktapur drove each other toward architectural magnificence, commissioning increasingly elaborate temples and palace complexes until conquest ended the competition.

What makes Patan exceptional is density. Hindu temples and Buddhist monasteries crowd a single architectural ensemble—Krishna Temple’s distinctive North Indian shikhara style rising amid pagoda-roofed shrines to Bhimsen and Vishwanath, the Royal Palace with intricate wooden windows and gilded copper roofs creating vertical drama. Religious synthesis becomes spatial reality: Hindu and Buddhist sacred architecture sharing the same square, Newari craftsmen serving both traditions simultaneously.

The 2015 Gorkha earthquake devastated this heritage. The Krishna Temple survived (stone construction held), but other structures collapsed completely. Masumi’s photograph may document pre-earthquake architecture now altered or destroyed—making this work historical record as well as art.

Her panoramic collage technique suits the square’s complexity. Multiple temples in proximity, multi-courtyard palace buildings, ornate architectural details competing for attention—no single viewpoint captures the ensemble. She assembles the fragments into comprehensive documentation, showing how centuries of patronage created sacred architecture at extraordinary concentration.

Patan remains a living landscape. Pilgrims circumambulate temples, vendors sell offerings, residents conduct daily life within World Heritage context. The architecture still serves its original functions despite the damage—sacred space persisting through catastrophe.