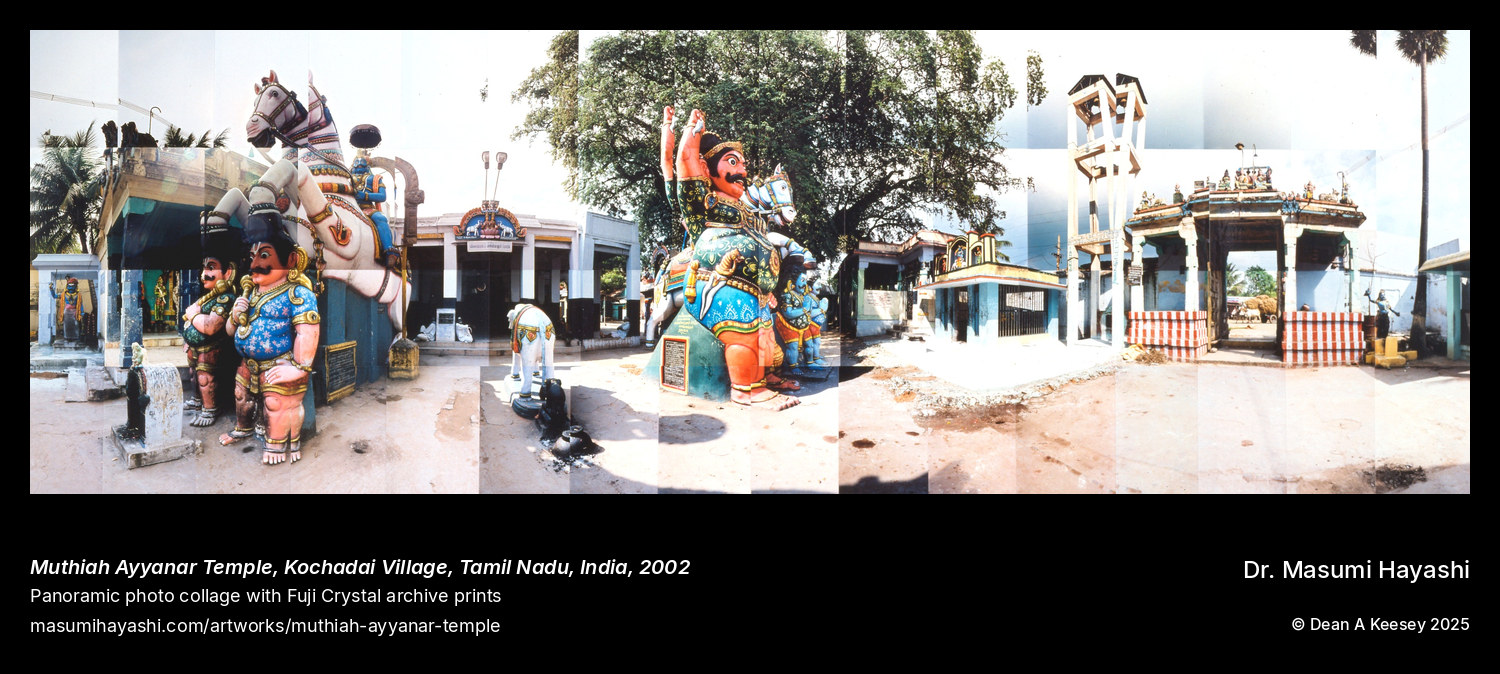

Muthiah Ayyanar Temple, Kochadai Village, Tamil Nadu, India

Kochadai Village, Madurai, Tamil Nadu, India

Panoramic Photo Collage

2002

53 x 19

This 53-by-19-inch horizontal panorama documents a rural folk deity shrine in Kochadai village near Madurai, representing a dramatic departure from the Sacred Architectures series’ predominant focus on grand brahmanical temples and UNESCO World Heritage monuments. Here Hayashi captures Tamil folk Hinduism’s village guardian worship where monumental terracotta horses—sometimes over twenty feet tall—stand arrayed before humble brick shrines marking village boundaries and protecting agricultural communities from demons, disease, and malevolent spirits through Ayyanar’s fierce guardianship.

Ayyanar functions as village guardian deity throughout Tamil Nadu: typically enshrined in simple open-air compounds at village edges or agricultural field boundaries where terracotta horse vahanas (divine vehicles) stand before modest shrines. Devotees pledge terracotta horses when seeking Ayyanar’s protection, commissioning them from village potters when prayers are answered. Shrines accumulate dozens to hundreds of horses over decades, creating landscapes of votive offerings in various states of decay as monsoon rains and sun gradually weather the terracotta while new horses replace old.

Unlike brahmanical temples requiring Brahmin priests and Sanskrit rituals, Ayyanar worship represents non-Brahmin tradition managed by village agricultural communities through Tamil-language prayers, oral traditions, and annual festivals where the deity possesses mediums who speak prophecies to assembled villagers. This folk religious practice predates Aryan-Brahmanical Hinduism’s arrival in South India, maintaining indigenous Dravidian worship forms despite later attempts at absorption into Sanskritic genealogies.

Created in 2002 during Hayashi’s concentrated Tamil Nadu documentation, the work reveals sophisticated understanding that Tamil religious landscape cannot be comprehended solely through stone gopurams and thousand-pillar halls but requires documenting folk traditions practiced by majority rural Tamils. The horizontal format captures terracotta horses arranged in procession, the village compound’s lateral extent, or agricultural landscape context where sacred and cultivated space interpenetrate at civilization’s permeable boundary with wilderness.