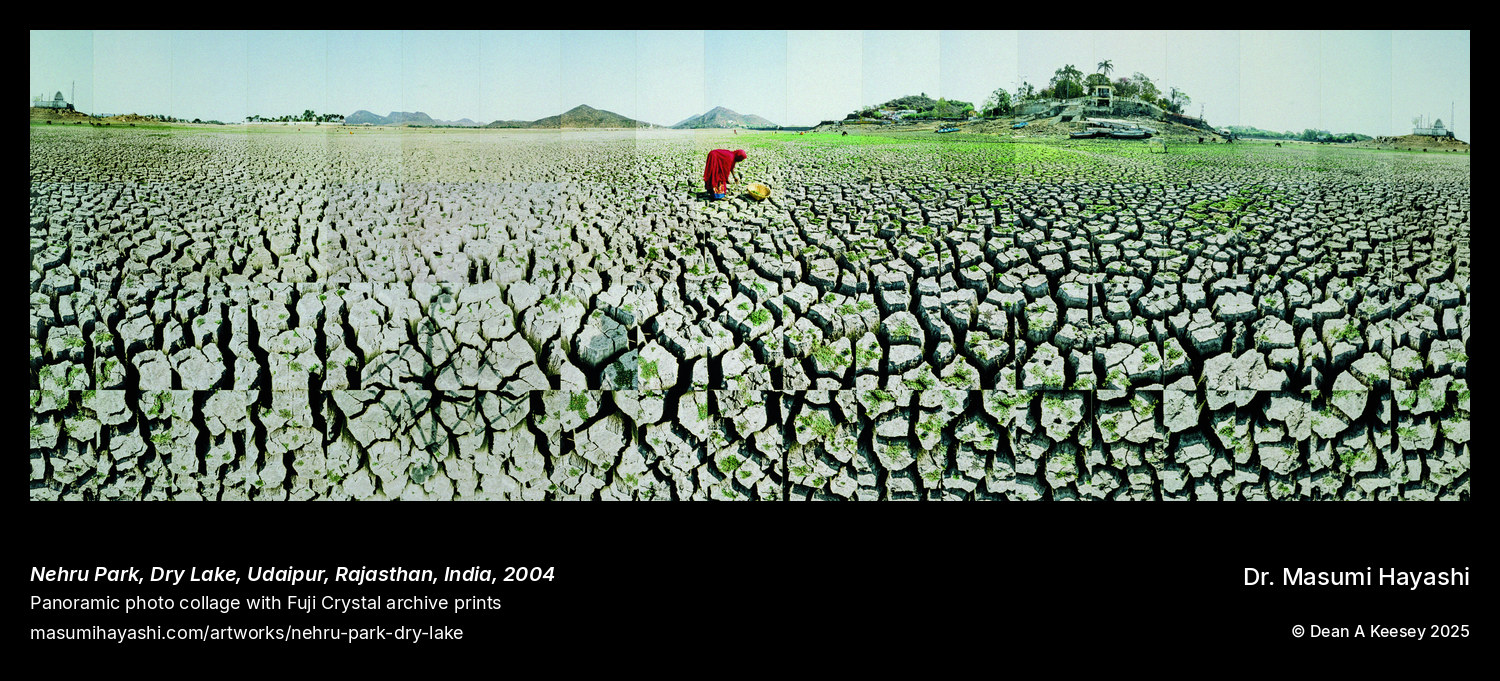

Dry Lake, Nehru Park, Udaipur, Rajasthan, India

Fateh Sagar Lake, Udaipur, Rajasthan, India

Panoramic Photo Collage

2004

18" x 57"

Udaipur calls itself the “City of Lakes,” the “Venice of the East,” marketing romantic palace-and-lake imagery to tourists seeking Rajasthani splendor. Mewar rulers engineered four major artificial lakes beginning in 1559, creating oasis city amid Thar Desert aridity. Then the water disappears. Fateh Sagar Lake drains to cracked mud. Nehru Park—normally accessible only by boat—becomes landlocked island in desert basin. Ghat steps descend from embankment walls toward lakebed that should be submerged but instead bakes under Rajasthani sun. In 2004, Hayashi photographed environmental catastrophe masquerading as picturesque tourism destination.

The format announces crisis: 18 by 57 inches, the narrowest work in her entire Sacred Architectures series. The 18-inch width constricts more severely than any other piece—narrower than River Ganges at Varanasi, narrower than the Okunoin cemetery paths, narrower than any temple documentation. The towering 57-inch height emphasizes vertical distance when the lake drains from its maximum 13.4-meter depth, exposing infrastructure designed to remain underwater. This isn’t the horizontal panorama expected for lake documentation. It’s vertical format subverting expectations, capturing exposed descent, revealed foundations, the architectural evidence of water that isn’t there.

Udaipur’s drought follows documented pattern: 2000, 2002, 2009, 2012, 2016, 2019. Recurring cycles threaten water supply, agricultural irrigation, cultural identity dependent on liquid presence. The title “Dry Lake” refuses euphemism. Not “low water levels” or “seasonal variation”—dry. Empty. Failed. The Sacred Architectures series expands here from timeless temple documentation to environmental crisis record. Most of Hayashi’s work captures architecture that has survived centuries, that will likely survive centuries more. This documents landscape failure, infrastructure exposed, sacred geography rendered incoherent when the defining element— water—vanishes.

The vertical narrowness serves environmental message. Constricted width suggests scarcity, compression, the closing-in feeling of resources disappearing. The height documents what drought reveals: full vertical extent of ghat staircases normally partially submerged, embankment walls designed to contain water now framing dust, park architecture becoming landlocked curiosity rather than island destination. Format and content merge into argument about climate fragility, about how quickly romantic tourism imagery collapses into crisis landscape, about what happens when oasis cities engineered against desert fail to maintain their founding premise.

Fateh Sagar Lake represents extraordinary engineering achievement—16th-century hydrological intervention creating permanent water source in environment naturally hostile to such ambition. The artificiality matters. These aren’t natural lakes suffering drought. They’re human construction demonstrating that building against climate eventually fails when precipitation patterns shift, when monsoons become unreliable, when populations grow beyond watershed capacity. The lake drains because human demands exceed replenishment rates, because tourism and agriculture and urban expansion consume water faster than sky delivers it.

The Smithsonian Institution acquired this work in 2018 via the Katz-Huyck collection, placing environmental documentation in America’s premier museum network. The acquisition recognizes Hayashi’s work beyond aesthetic architectural photography, acknowledging sacred landscape vulnerability and climate themes with urgent contemporary relevance. When she photographed this dry lakebed in 2004, she documented more than temporary drought. She captured preview of what happens when civilizations build oases in deserts, when sacred geography depends on hydrological systems vulnerable to climate change, when romantic tourism destinations reveal their environmental fragility through catastrophic drainage exposing infrastructure that was never supposed to see sunlight.