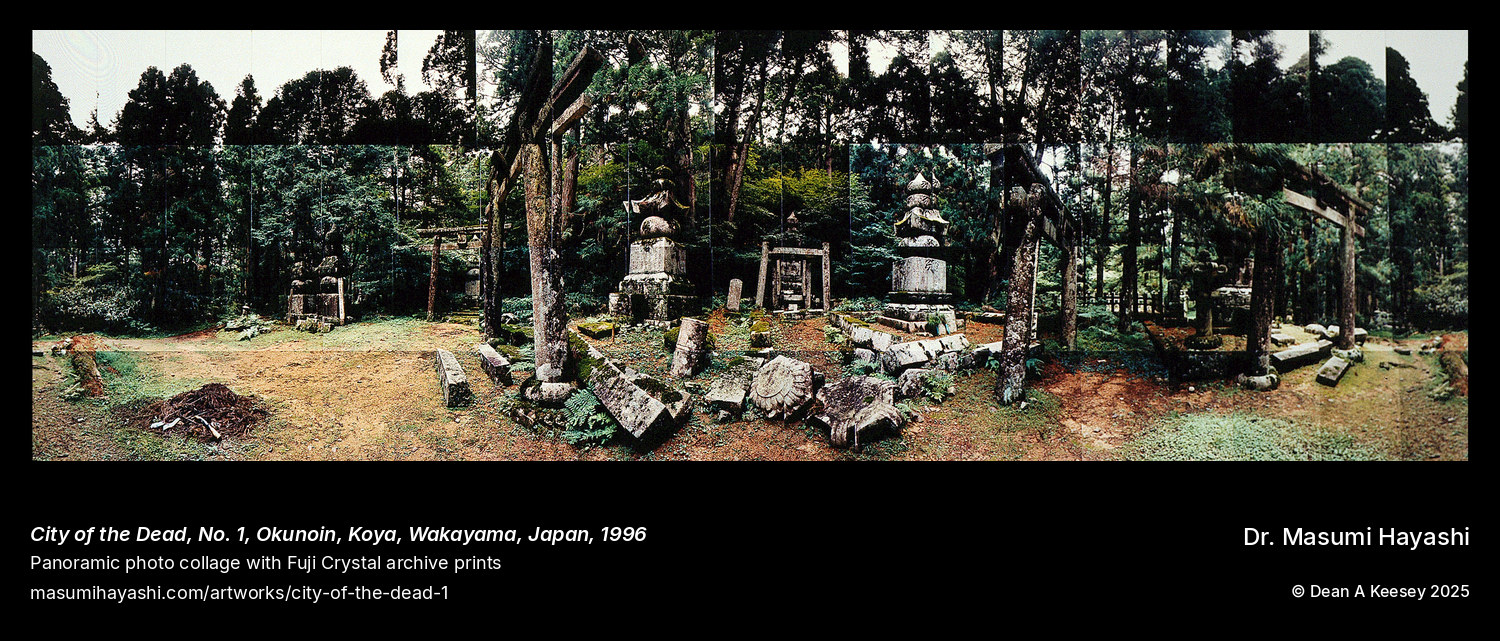

City of the Dead, No. 1, Okunoin, Koya, Wakayama, Japan

Okunoin, Koyasan, Japan

Panoramic Photo Collage

1996

17 x 53

Deep in the mountains of Wakayama Prefecture, over 200,000 graves crowd beneath towering cryptomeria cedars along a two-kilometer path to the mausoleum where Kukai—Kobo Daishi, founder of Shingon esoteric Buddhism—entered eternal meditation in 835 CE. Japanese Buddhists believe he remains alive in his tomb, awaiting Maitreya Buddha’s arrival. Monks have delivered two meals daily for 1,200 years. The food disappears, consumed or removed as ritual performance, evidence of continued presence. This isn’t metaphor or symbolic survival. The tradition asserts literal persistence: Kobo Daishi still breathes, still requires sustenance, still protects those buried near him. Proximity to his mausoleum ensures posthumous spiritual benefit, making Okunoin the most desirable final address in Japanese Buddhism.

In 1996, Hayashi photographed what that belief creates. The result— sprawling necropolis where feudal lords seeking redemption for lives of violence rest beside modern corporations honoring deceased employees through company memorials. Twelfth-century samurai stupas stand next to twenty-first-century monuments creating temporal disorientation, centuries layering atop each other beneath moss-covered stones and filtered forest light. The 17-by-53-inch format—among the narrowest widths in her entire series—captures the cemetery’s essential spatial character: vertical cedar trunks rising toward canopy, five-element gorinto stupas stacked representing earth-water-fire-wind-void, the path constricted between monuments closing in from both sides. The extreme narrowness isn’t aesthetic choice; it’s phenomenological documentation of what walking this path feels like, how 1,200 years of continuous burial creates claustrophobic beauty, how sacred forest architecture organizes descent from outer feudal grave areas toward the inner sanctuary where the saint sleeps his waking sleep.

This marks the first of two Okunoin works, sequential documentation recognizing that sites this complex require multiple perspectives. City of the Dead No. 2 (also 1996, identical 17x53 dimensions) captures complementary views along the pilgrimage route, different atmospheric conditions, varied sections revealing the cemetery’s depth and diversity. The two-work strategy establishes pattern Hayashi later employs at Airavatesvara Temple, Meenakshi Temple, Angkor Wat—major monuments demanding serial treatment, different compositional approaches, architectural elements isolated for study.

What makes Okunoin extraordinary within Japanese Buddhist death culture is how it embodies wabi-sabi aesthetic principles—beauty in impermanence, aging, decay—while simultaneously claiming immortal presence at its center. The cemetery celebrates transience: weathered wooden markers, crumbling stone, moss consuming everything, forest reclaiming monuments through patient vegetative encroachment. Yet at the path’s end sits evidence against mortality: a saint who doesn’t die, who requires feeding, whose continued meditation interrupts the natural cycle the cemetery otherwise documents so comprehensively. This paradox—decay everywhere except where it matters most—creates philosophical tension that 1,200 years of burials haven’t resolved.

As 1996 work, this predates Hayashi’s major India-Cambodia-Nepal journey by four years, establishing Japanese Buddhist sites as foundational to her Sacred Architectures exploration. UNESCO designated Mount Koya World Heritage in 2004, recognizing it as Shingon Buddhism’s headquarters. But the cemetery’s power derives from living tradition, from belief specific enough to require daily food delivery, from conviction that burial location affects posthumous trajectory. When Hayashi photographed these moss-covered stones beneath ancient cedars, she documented more than architectural beauty. She captured how sacred space organizes itself around claims of ongoing miracle, how 200,000 graves arrange themselves in concentric urgency radiating from a mausoleum where monks insist—despite all evidence of decay surrounding them—death failed to claim its most important resident.