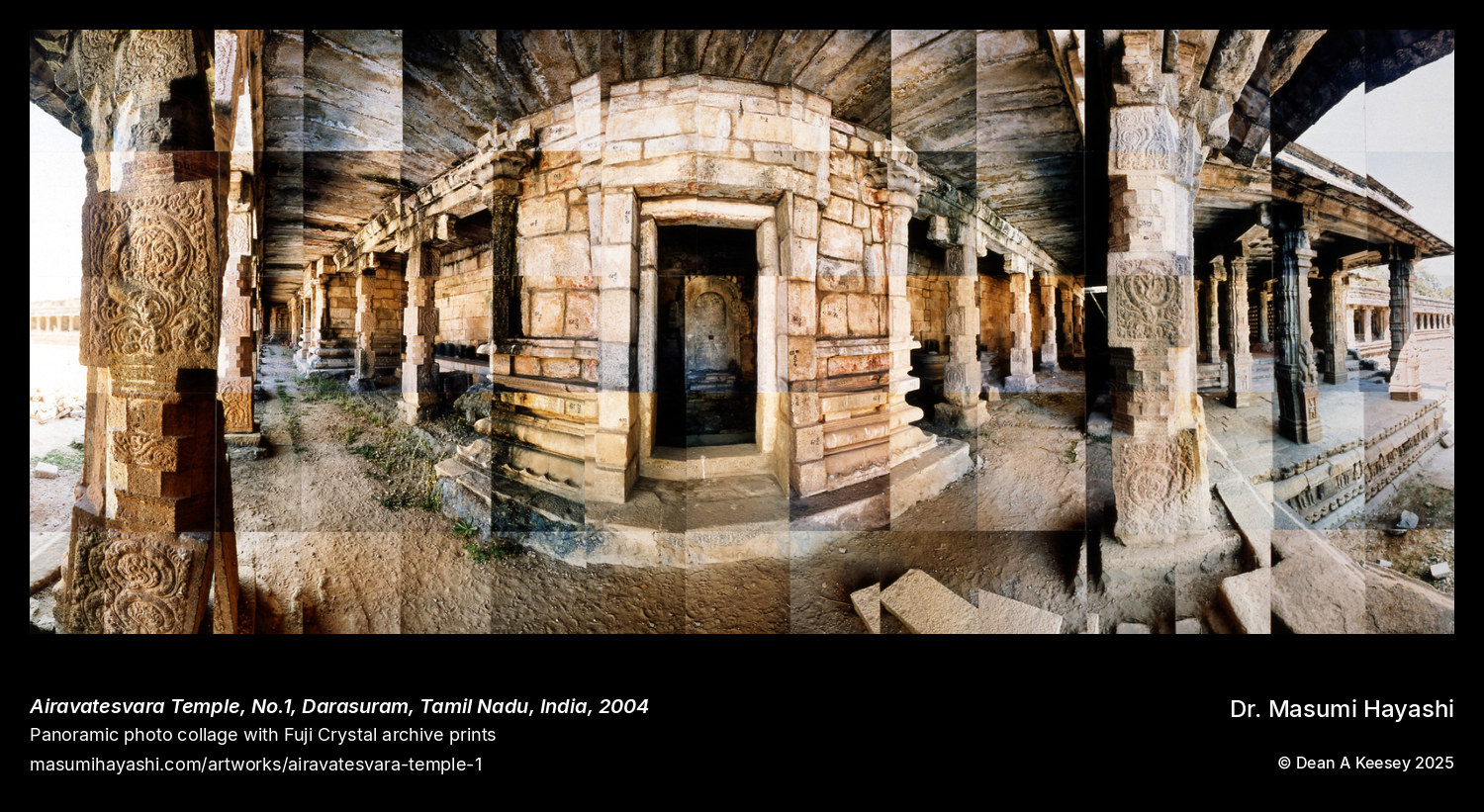

Airavatesvara Temple

Darasuram, Tamil Nadu, India

Panoramic Photo Collage

2004

23" x 50"

Where the horizontal panorama captures courtyard relationships and the celebrated chariot pavilion, this vertical perspective documents the temple’s vimana tower. The 23-by-50-inch format compresses horizontal breadth while emphasizing architectural height, directing visual attention upward along the pyramidal superstructure and its intricate carved tiers. Complementary viewpoint on the same UNESCO World Heritage monument.

Chola architects perfected the pyramidal vimana: towering superstructure rising above the sanctum in diminishing tiers, each layer articulated with architectural detail and sculptural ornamentation. This vertical emphasis creates visual monumentality even in relatively compact temple plans. Unlike traditions spreading horizontally through courtyard expansion, Chola architecture builds upward, stacking carefully proportioned levels to achieve spiritual and aesthetic effect.

Airavatesvara’s vimana rises through disciplined tiers. Each level defined by pilastered walls, sculpted niches housing deities, projecting cornices creating rhythmic horizontal accents within overall vertical thrust. What could be simple pyramidal mass becomes complex sculptural composition readable from ground level. Surface articulation transforming architectural function into artistic achievement.

The vimana functions as three-dimensional theological text. Sculptural programs presenting elaborate iconographic schemes: directional deities guarding cardinal points, various Shiva manifestations in sculpted niches, celestial beings articulating architectural transitions. Visual theology communicated through form and content rather than textual instruction. Devotees circumambulating the temple encounter this imagery sequentially, physical movement coordinated with visual consumption of theological content.

The pairing of contrasting formats ensures comprehensive spatial documentation impossible within single viewpoint. Together, these 2004 works capture the temple at moment of international recognition—UNESCO World Heritage inscription—while documenting continued local devotional function. Ancient origin, living practice.