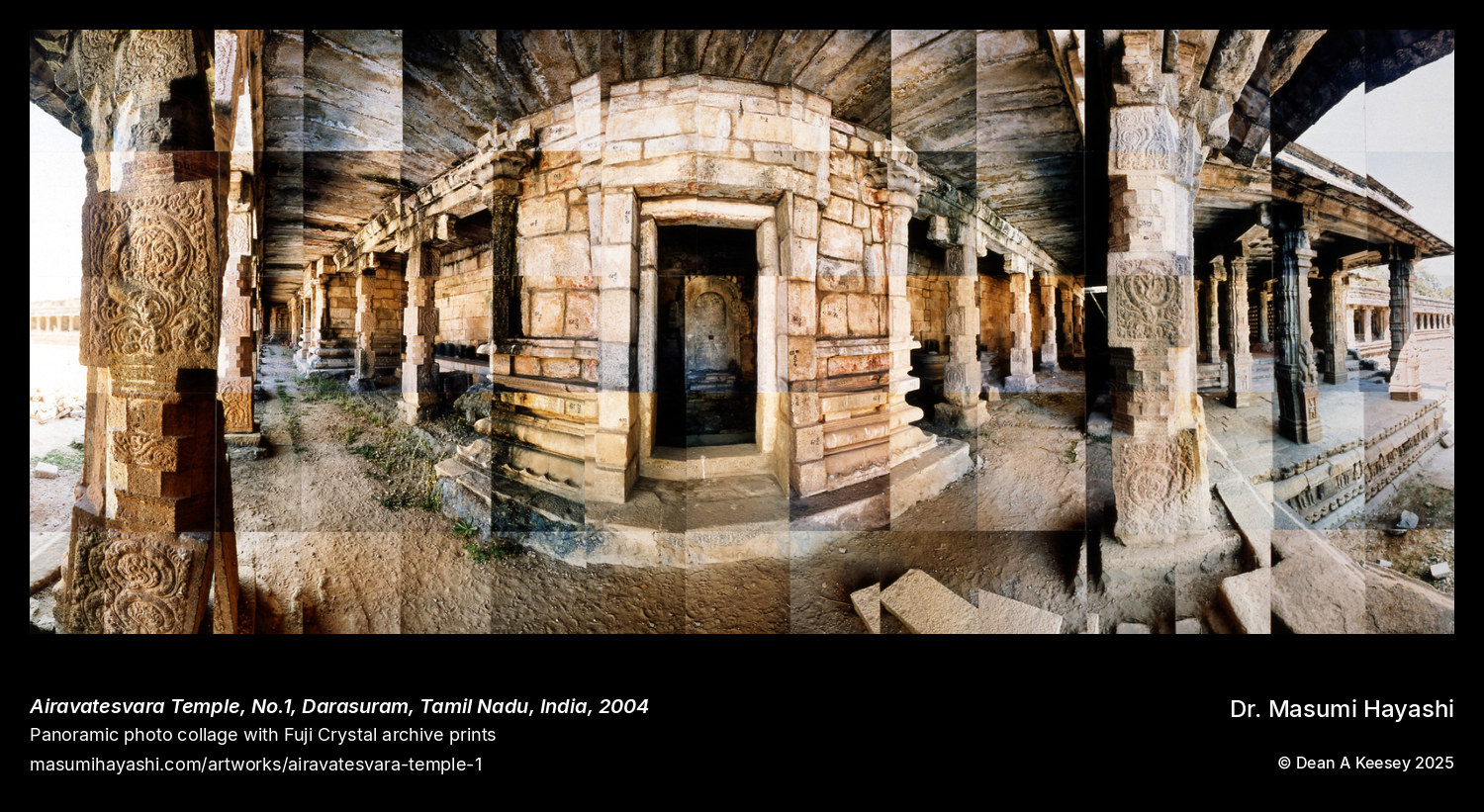

Airavatesvara Temple

Darasuram, Tamil Nadu, India

Panoramic Photo Collage

2004

53" x 24"

Airavatesvara Temple demonstrates what Chola architects achieved when refinement mattered more than scale. Built by Rajaraja Chola II in the twelfth century, the temple captivates through proportion, intricate carving, architectural playfulness. Where earlier Chola monuments at Thanjavur and Gangaikonda Cholapuram overwhelm through sheer size, Airavatesvara achieves monumentality through artistic excellence. This is masterwork at intimate scale.

The temple’s celebrated feature: stone chariot pavilion fronting the main shrine. The entire mandapa conceived as Shiva’s chariot, complete with intricately carved wheels, prancing horses, elaborate architectural details transforming structural necessity into mythological narrative. Chola sculptural virtuosity fully realized. The horizontal format’s 53-inch width encompasses the chariot pavilion’s lateral extension and surrounding sculptural program, documenting courtyard relationships and visual connections between temple components.

Musical steps offer another innovation. Granite stairs producing musical tones when struck. Acoustic design integrated into sacred architecture. Chola understanding of temples as multisensory devotional environments: sight, sound, spatial experience coordinated in worship practice. Architecture engaging multiple senses simultaneously.

This 2004 documentation coincides exactly with UNESCO’s formal inscription of the “Great Living Chola Temples”—Airavatesvara joining Thanjavur and Gangaikonda as World Heritage sites. The designation recognizes both architectural achievement and continuing function. Nine centuries of unbroken devotional tradition. Ancient origin continuously renewed through living religious practice. Temple serving local Shaivite worship while recognized as monument of universal cultural significance.

Hayashi photographed during intensive South Indian temple documentation campaign, capturing Chola dynasty’s architectural maturity: confidence, technical mastery, artistic ambition realized through refinement rather than overwhelming scale.