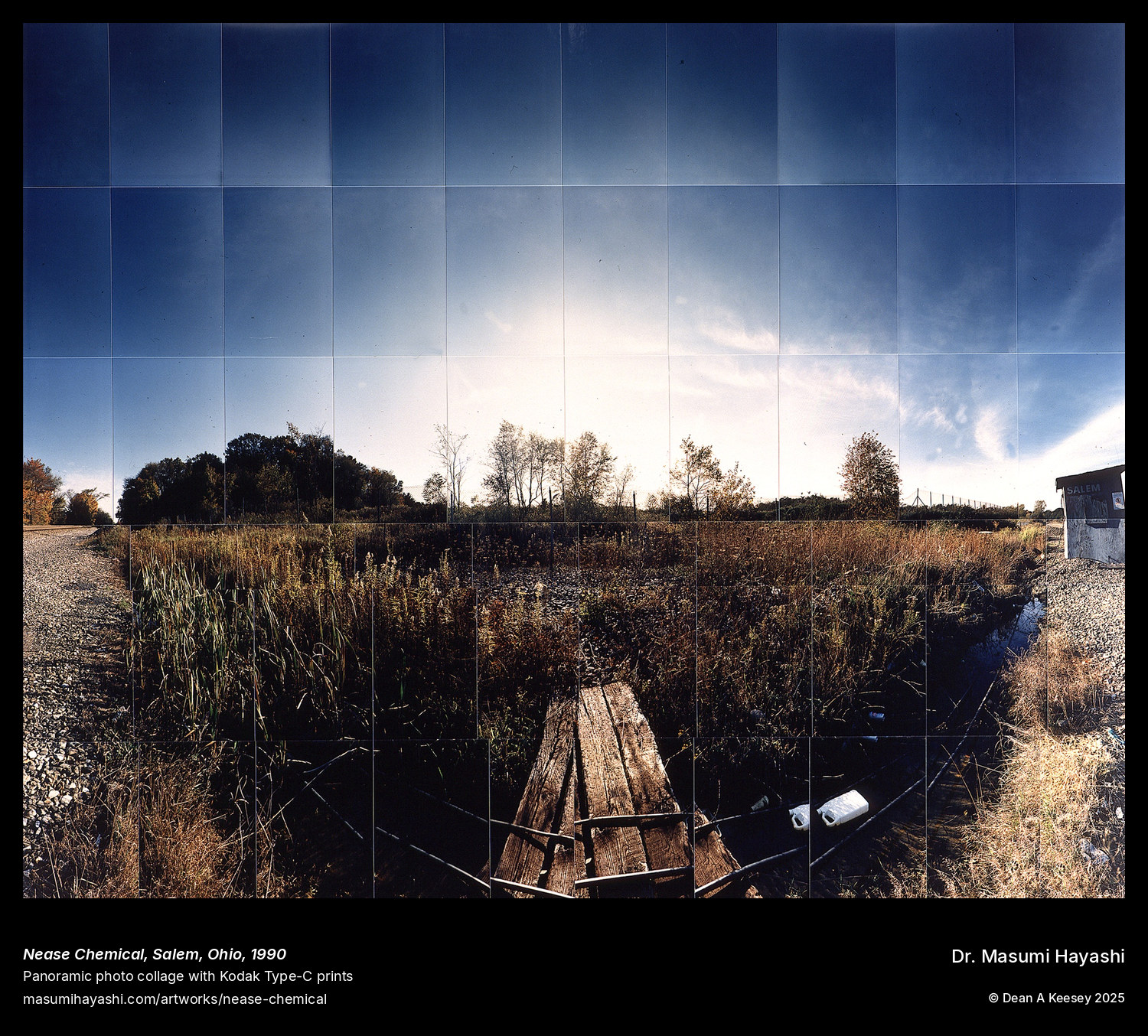

Nease Chemical, Salem, Ohio

Salem, OH, USA

Panoramic Photo Collage

1990

31 x 26

Nease Chemical in Salem represents ordinary chemical plant contamination that affected hundreds of communities across America’s industrial heartland—sites lacking Love Canal’s notoriety or nuclear facilities’ dramatic narratives, yet imposing identical toxic burdens on working-class neighborhoods that hosted them.

Salem in Columbiana County sits midway between Pittsburgh and Cleveland with rail access to major manufacturing centers. The facility likely operated from the 1940s through 1980s, decades when chemical production expanded dramatically while environmental regulation remained minimal. Companies disposed of solvents, heavy metals, and organic chemical compounds through methods maximizing cost savings while externalizing environmental costs: unlined surface impoundments, direct discharge to waterways, dumping onto soil that allowed contaminants to migrate into groundwater.

The Nease name suggests family or private ownership rather than corporate conglomerate—a pattern influencing contamination legacies. When privately-held chemical companies ceased operations or declared bankruptcy, cleanup responsibility fell to EPA Superfund programs rather than corporate successors. The pattern repeated nationwide: companies captured profits during operational years while communities inherited contamination requiring federal intervention decades later.

Hayashi’s 1990 documentation captured sites during transitional periods when northeastern Ohio chemical facilities were closing due to foreign competition, stricter regulations increasing costs, and industry consolidation rendering older plants economically unviable. Her photography documents the abandoned phase—production ended, employment lost, buildings deteriorating—before comprehensive cleanup began. These images preserve evidence of industrial decline’s environmental dimensions.

The work reveals industrial development’s hidden costs: chemical manufacturing that generated employment and community economic stability during operational decades left contamination persisting long after plants closed and jobs disappeared. Communities gained temporary economic benefits; they inherited permanent environmental burdens requiring multi-generational remediation efforts funded by taxpayers rather than the corporations that profited.

This pattern created northeastern Ohio’s toxic geography that Hayashi systematically mapped: Nease, Industrial Excess Landfill, Summit National, Republic Steel Quarry forming regional contamination constellation affecting working-class communities lacking political influence to resist facility siting or demand corporate accountability for cleanup costs.