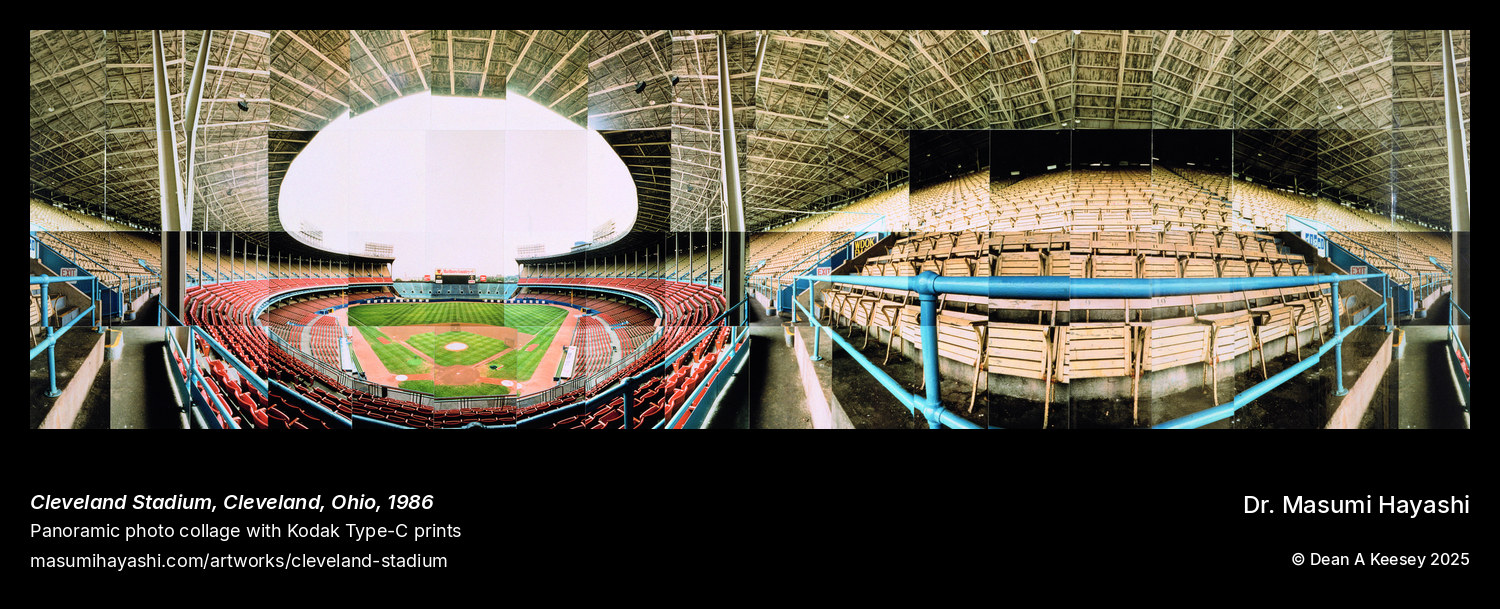

Cleveland Stadium, Cleveland, Ohio

Cleveland, OH, USA

Panoramic Photo Collage

1986

18 x 61

Cleveland Municipal Stadium opened in 1931 as a Depression-era act of civic faith—78,000 seats of poured concrete rising from the Lake Erie shore, built when the city couldn’t really afford it but needed to believe in itself anyway. For sixty years it held the Indians and the Browns, the civic rituals of baseball and football that bound generations of Clevelanders to this massive, flawed, beloved structure.

By 1986 when Masumi photographed it, the stadium was caught between eras. The concrete was crumbling. The sight lines were terrible—too far from the baseball diamond, awkward angles for football. The luxury boxes that modern sports economics demanded didn’t exist. Replacement discussions had begun, though demolition was still a decade away.

Masumi captured the stadium in this transitional moment, still functional but already elegiac. Her panoramic format stretches across 61 inches, matching the stadium’s own horizontal monumentality—those endless grandstands that made you turn your head to take it all in. The photo collage technique assembles dozens of individual photographs into a single composition, creating the same fractured-yet-unified experience of actually being there, eyes scanning across that vast concrete bowl.

What the photograph preserves is something photographs rarely capture: the experience of public space at civic scale. The stadium was democratic architecture—the cheap seats and the expensive seats all under the same sky, watching the same game, part of the same crowd. When it came down in 1996, replaced by smaller, more profitable venues, that particular kind of shared urban experience went with it.

The Rock & Roll Hall of Fame stands on the site now. Masumi’s photograph remains as one of the most detailed visual records of what was there before—not just the architecture, but the idea of the stadium as common ground, a place where a city gathered to be a city together.